Recently, a dear friend of Pitts Theology Library passed away. John August Swanson, whose artwork graces the walls of Pitts Theology Library and Candler School of Theology, was 83 years old. In 2008, Candler became a home for Swanson’s artwork when it put on permanent display more than 50 pieces of Swanson’s prints and paintings. The following year Swanson chose to deposit his archives at Pitts Theology Library.

J ohn August Swanson was born in Los Angeles in 1938 to parents who had immigrated to the United States – his mother was from Mexico and his father from Sweden. While a student at UCLA in the 1960s, Swanson became increasingly interested in political and social issues and began creating posters. In 1967, Swanson studied with Corita Kent at Immaculate Heart College. Corita’s serigraphs (screen prints) were bold and colorful – features also found in Swanson’s early work. Just like Corita, Swanson would adopt the serigraph as his primary medium. From the late 1960s to the 1980s, Swanson’s serigraphs became increasingly more complex and innovative. They became known for their intricately detailed layering of ink, each requiring their own stencils and screens. He typically employed 30 to 50 (or more!) printing layers in each of his serigraphs, thus taking him multiple months to produce an edition. These serigraphs are vivid, colorful, highly technical, but also organic.

ohn August Swanson was born in Los Angeles in 1938 to parents who had immigrated to the United States – his mother was from Mexico and his father from Sweden. While a student at UCLA in the 1960s, Swanson became increasingly interested in political and social issues and began creating posters. In 1967, Swanson studied with Corita Kent at Immaculate Heart College. Corita’s serigraphs (screen prints) were bold and colorful – features also found in Swanson’s early work. Just like Corita, Swanson would adopt the serigraph as his primary medium. From the late 1960s to the 1980s, Swanson’s serigraphs became increasingly more complex and innovative. They became known for their intricately detailed layering of ink, each requiring their own stencils and screens. He typically employed 30 to 50 (or more!) printing layers in each of his serigraphs, thus taking him multiple months to produce an edition. These serigraphs are vivid, colorful, highly technical, but also organic.

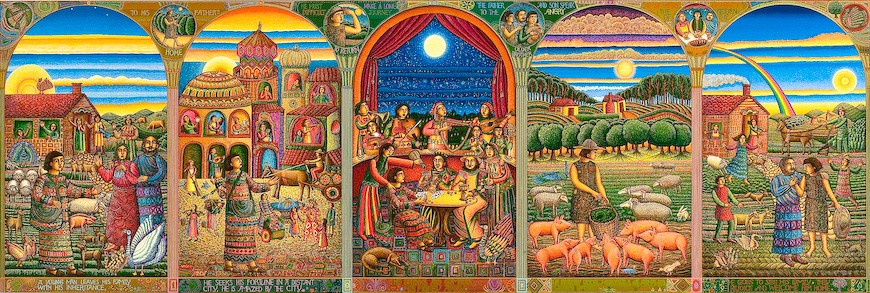

Swanson often said that his art is his most social act. For him there was no hierarchical structure of human worth. He elevated people in various trades and positions that were often thought of as being mundane or menial. For Swanson, the woman ironing clothes had as much dignity or worth as a statesman. He championed specific political and social causes either indirectly through various prints or overtly with posters dealing with topics like immigration, racism, the death penalty, nuclear proliferation, and healthcare. His artwork promoted various performance arts such as the theatre or the circus as well. What brought Swanson the most attention, however, was his treatment of biblical stories and scenes. In his own words, his influences included “imagery of Islamic and medieval miniatures, Russian iconography, the color of Latin American folk art, and the tradition of Mexican muralists.”

The library holds specimens of Swanson’s artwork spanning his whole career – from 1969 to 2021. The collection not only contains finished works of art, but it also demonstrates how the artist created his pieces. Individual layers of prints are retained which function as witnesses to the way that pieces of art progressed in the studio. Various color proofs, progressive proofs, stencils, drawings, and color tests complement the completed pieces. In addition to serigraphy, Swanson also utilized lithography, painting, engraving, and etching. In the last decade of his life, he shifted his focus to giclées and posters. The collection at Pitts Theology Library contains examples from all of these media. Staff at the library frequently use the Swanson collection for instruction and exhibition and researchers can schedule appointments to view the collection as well.

The library holds specimens of Swanson’s artwork spanning his whole career – from 1969 to 2021. The collection not only contains finished works of art, but it also demonstrates how the artist created his pieces. Individual layers of prints are retained which function as witnesses to the way that pieces of art progressed in the studio. Various color proofs, progressive proofs, stencils, drawings, and color tests complement the completed pieces. In addition to serigraphy, Swanson also utilized lithography, painting, engraving, and etching. In the last decade of his life, he shifted his focus to giclées and posters. The collection at Pitts Theology Library contains examples from all of these media. Staff at the library frequently use the Swanson collection for instruction and exhibition and researchers can schedule appointments to view the collection as well.

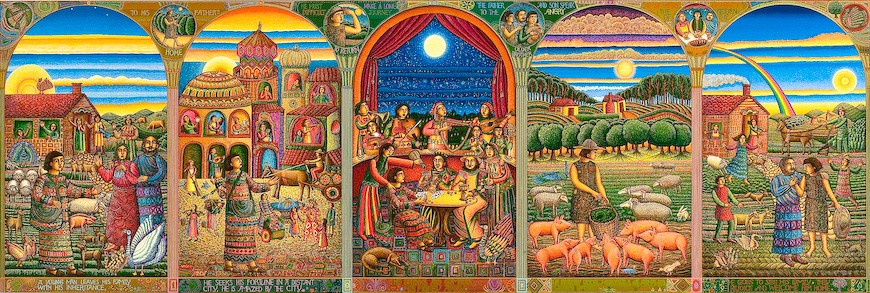

One of the things I appreciate about Swanson’s art is that he often tries to tell a narrative instead of capturing a single moment in time. For instance, whereas Rembrandt and others have painted works based on Jesus’ parable of the prodigal son, they often focus on a single moment, such as the reunification of the son with the father. However, in Swanson’s telling of the parable in his serigraph, Story of the Prodigal Son (2004), he includes five main panels depicting episodes within the parable: (1) departure from home, (2) travel to a distant city, (3) recklessly spent fortune, (4) famine and feeding pigs, and (5) a return to home. It also contains four smaller images highlighting themes from the parable. The person viewing this print is reminded of the entire parable and its progression as a story rather than a single snapshot in time. Story of the Prodigal Son is one of my favorite Swanson pieces and it hangs on the wall in our home office.

As the Curator of Archives and Manuscripts at Pitts Theology Library, I’ve worked closely with the Swanson materials in our collection by describing them, making them accessible to researchers, and sharing them with various classes and visitors to the library. From the start, I found Swanson’s artwork very appealing especially due to the technical prowess needed to create these elaborate serigraphs. Yet the artwork affected me further once I got to know the artist himself. I’ve enjoyed having various phone conversations with John and visiting him in his Los Angeles studio. Most of our conversations discussed the types of materials that should be included in his archives. Yet we always discussed the specifics of his art and John would often ask whether I liked a certain piece. This wasn’t John’s way of fishing for a compliment. He genuinely wanted to know how his artwork speaks to people because his art was his ministry. It was less about the aesthetics and more about how people interpret the stories presented in his art. The hospitality John shared with me profoundly mirrored the hospitality one reads about in Scripture. One couldn’t visit John without sharing a meal that included fruit from his garden. John had a generous heart and spirit that was always made evident in the causes he took up and the works that he so beautifully created.

By Brandon Wason, Curator of Archives and Manuscripts

—

The finding aid for the John August Swanson papers and artwork can be found here: http://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/rmnvd

Dr. Smith goes on to admit “The Candy House doesn’t feel revelatory in quite the same way. But it lets us connect with those characters again. And it extends Egan’s meditations on memory, authenticity, and more through updated engagements with a next wave of technologies, including social media, artificial intelligence, and what Shoshana Zuboff has called

Dr. Smith goes on to admit “The Candy House doesn’t feel revelatory in quite the same way. But it lets us connect with those characters again. And it extends Egan’s meditations on memory, authenticity, and more through updated engagements with a next wave of technologies, including social media, artificial intelligence, and what Shoshana Zuboff has called

ohn August Swanson was born in Los Angeles in 1938 to parents who had immigrated to the United States – his mother was from Mexico and his father from Sweden. While a student at UCLA in the 1960s, Swanson became increasingly interested in political and social issues and began creating posters. In 1967, Swanson studied with Corita Kent at Immaculate Heart College. Corita’s serigraphs (screen prints) were bold and colorful – features also found in Swanson’s early work. Just like Corita, Swanson would adopt the serigraph as his primary medium. From the late 1960s to the 1980s, Swanson’s serigraphs became increasingly more complex and innovative. They became known for their intricately detailed layering of ink, each requiring their own stencils and screens. He typically employed 30 to 50 (or more!) printing layers in each of his serigraphs, thus taking him multiple months to produce an edition. These serigraphs are vivid, colorful, highly technical, but also organic.

ohn August Swanson was born in Los Angeles in 1938 to parents who had immigrated to the United States – his mother was from Mexico and his father from Sweden. While a student at UCLA in the 1960s, Swanson became increasingly interested in political and social issues and began creating posters. In 1967, Swanson studied with Corita Kent at Immaculate Heart College. Corita’s serigraphs (screen prints) were bold and colorful – features also found in Swanson’s early work. Just like Corita, Swanson would adopt the serigraph as his primary medium. From the late 1960s to the 1980s, Swanson’s serigraphs became increasingly more complex and innovative. They became known for their intricately detailed layering of ink, each requiring their own stencils and screens. He typically employed 30 to 50 (or more!) printing layers in each of his serigraphs, thus taking him multiple months to produce an edition. These serigraphs are vivid, colorful, highly technical, but also organic. The library holds specimens of Swanson’s artwork spanning his whole career – from 1969 to 2021. The collection not only contains finished works of art, but it also demonstrates how the artist created his pieces. Individual layers of prints are retained which function as witnesses to the way that pieces of art progressed in the studio. Various color proofs, progressive proofs, stencils, drawings, and color tests complement the completed pieces. In addition to serigraphy, Swanson also utilized lithography, painting, engraving, and etching. In the last decade of his life, he shifted his focus to giclées and posters. The collection at Pitts Theology Library contains examples from all of these media. Staff at the library frequently use the Swanson collection for instruction and exhibition and researchers can schedule appointments to view the collection as well.

The library holds specimens of Swanson’s artwork spanning his whole career – from 1969 to 2021. The collection not only contains finished works of art, but it also demonstrates how the artist created his pieces. Individual layers of prints are retained which function as witnesses to the way that pieces of art progressed in the studio. Various color proofs, progressive proofs, stencils, drawings, and color tests complement the completed pieces. In addition to serigraphy, Swanson also utilized lithography, painting, engraving, and etching. In the last decade of his life, he shifted his focus to giclées and posters. The collection at Pitts Theology Library contains examples from all of these media. Staff at the library frequently use the Swanson collection for instruction and exhibition and researchers can schedule appointments to view the collection as well.